By Jean Haalbloom

Let me be clear. I have no love for the Sears store building at Fairview Park mall in Kitchener. Then again how many Kitchener residents shared a love for Kitchener’s old city hall. Even its architect, the late William Henry Eugene Schmalz, could not convince councillors and Kitchener citizens to stop its demolition. After all, the Market Square shopping mall would revitalize Kitchener downtown; it would stimulate economic development. Instead, what we got was downtown’s demise with a 40-year struggle to recover using taxpayers’ investment dollars.

We are a community that enjoys reinventing ourselves. We pride ourselves on innovation. We were one of the first to develop a method of recycling garbage — the blue box. Then why as a community do we not insist on recycling our old buildings, even those from the 1960s. When we willingly replace our place-making heritage buildings, why do we accept a replay of reasons: doesn’t accommodate the workplace environment; it’s too hard to heat; it doesn’t fit the budget. None of these are heritage related reasons for demolition. Will replacing the Sears building truly make cash registers ring in the long-term? Who knows?

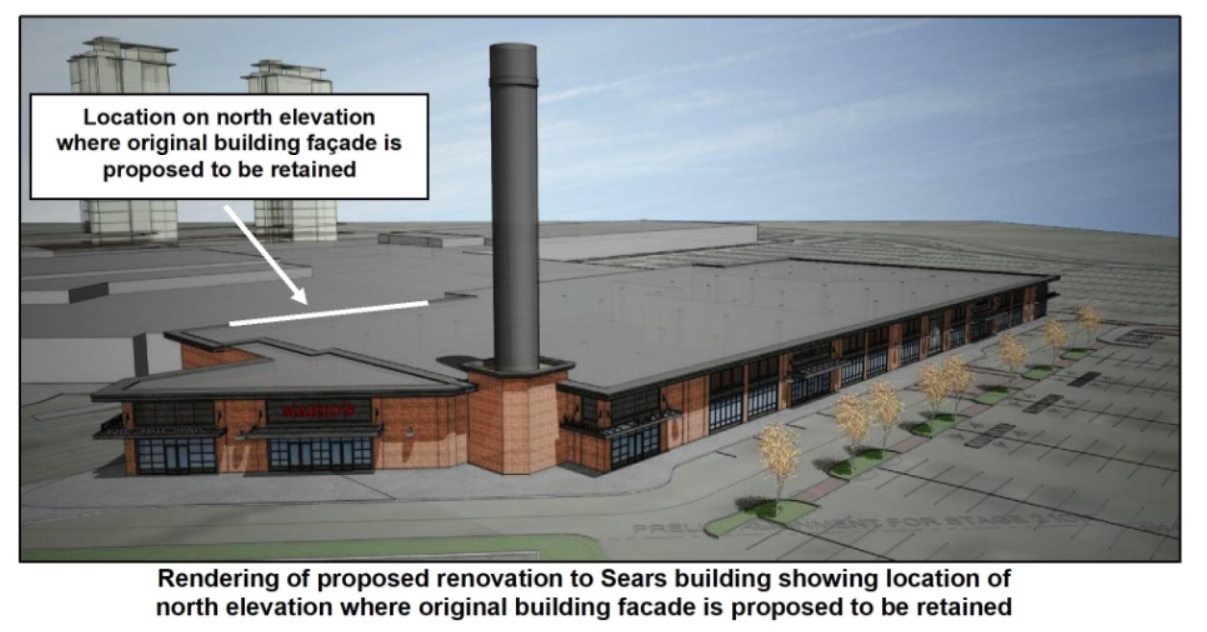

Further, if we pride ourselves on innovation, why do we embrace fake. Everywhere, we see fake muntin bars — those plastic bars that give windows the appearance of six over six panes of glass. And now we are contemplating replacing the Sears building with a fake water tower and smoke stack. And did you hear the sighs in Kitchener’s council chamber — ah yes, terrific, such a great investment offer to this community?

Perhaps, we should borrow a development page from our neighbouring province of Quebec. Year after year, many Quebec teams of architects, engineers, businesses and owners of old buildings are recognized at the annual conference of National Trust for Canada for innovative ways of reusing and restoring historic building. Here is one example: in Quebec City, on the periphery of the historic district sits a decommissioned church; the church is the size of our Trinity United at the corner of Frederick and Duke streets in downtown Kitchener. Concerned that this area of Quebec City had no community centre or place where troubled youth could experience sports, arts and culture, an entrepreneur had a dream of establishing a training ground for performers of the Cirque du Soleil. All he needed was a location. After a structural evaluation of the church’s bones, he learned that the structure offered a perfectly strong frame for the wires necessary to support acrobatics. Today, L’École de cirque de Quebec offers youth opportunities in a remarkable old church building.

So what’s the lesson? Whether or not you are impressed with the history or architecture of Trinity United or the Sears building, they have put their stamp on our sense of place. They demonstrate the tastes of the time. New does not always mean better. For 15 years, ‘new’ generally attracts us. Then our tastes change and new falls into distaste. Surely, we can use our innovative talents and thriftiness to demand reuse instead of destruction.

Jean Haalboom is a Kitchener resident, former city and regional councillor, and member of National Trust for Canada and Architectural Conservancy of Ontario.